Which Internet Service Is Better Netzero Or Juno

Today in Tedium: People want an improbable bargain, no matter how unlikely that bargain might actually be. Hence the potent interest in MoviePass, a company with a model so doomed that people were suggesting it would initially fail not long later on information technology started offering free daily tickets at $ix.99 per month. (Instead, its fast pass up took virtually a yr, fifty-fifty with a loftier fire rate, and now the company is changing its model considering it has no other option.) The fast decline of MoviePass got me thinking of another concept with a similar arc, one that hinged on a similar bet: The numbers would eventually piece of work themselves out. I'm, of course, talking about advert-supported dial-upwardly internet. Today's Tedium ties a thread between MoviePass, Juno, and NetZero. — Ernie @ Tedium

Enhance your paw if this device helped shape your childhood. (Lawrence Sinclair/Flickr)

The early days of the post-AOL internet were defined by schemes to offer internet at a deep discount

What are y'all willing to tolerate in exchange for something you go for "free"?

How far will you defile both yourself and your computer in an try to access something that other schmucks happily pay for?

The Gratuitous-Net model, which I wrote about earlier this year, pitched the idea of customs supported cyberspace, but information technology definitely wasn't a commercial model. For one thing, most Free-Nets could simply back up text-driven interfaces!

So this meant that entrepreneurs were looking to find different paths to monetize internet service in some manner, shape or form. In one instance, there was a company that tried to franchise out punch-up cyberspace service similar it was McDonald's or Burger Rex.

But there were lots of companies that saw an opportunity in free or extremely cheap net across Juno and NetZero.

One such service, Bigger.internet, offered a model reminiscent of MoviePass: Pay a one-time $59 fee, get complimentary internet forever, no questions asked, though definitely with some advertising. CEO Jeff Fortin was bullish, considering of course he was.

"Consumers volition finally realize cyberspace access is not something that has to cost $300 a year," he stated in a 1997 interview. "Other access providers are going to have to look at aligning themselves with a like program."

By Jan of 1998, there were already cracks showing in the model, with the company having to suspend new accounts on its website. Past Nov of that year, the competing Brigadoon.com, which distributed internet admission to nonprofits, bought Bigger.net for a not-and then-big price of $275,000. (Spoiler: Brigadoon.com is dead, as well, and leads to a simulated Adobe Flash site if yous load the URL.) Cincinnati's Tritium Network, which launched in 11 cities early on in 1998 and relied on a CNN Headline News-fashion ticker tape at the lesser of the browser screen (as well equally network backbone from Ohio's ain CompuServe), had shut down operations by November of that year.

The twelvemonth before that, a company chosen j3 Communications tried to bundle unlimited access with long distance service. Key word: Tried, considering the service lasted less than a calendar month.

These experiments failed for numerous reasons, including execution challenges and the sheer cost of offering a service that competing companies were getting paid a lot of money to offer. Punch-upwards internet access was non a commodity at this point, no matter how many attempts these companies made to make it so.

But somewhen, two companies got the model right enough that they became famous for offering free internet …supported, of course, by persistent, somewhat annoying ads.

2.6M

The number of users, at its summit, that Freeserve, the UK-based costless internet service, had. The model, which launched in 1998, was more than successful in Britain than in the U.S., in function because of a close necktie to the electronics retailer Dixons, and in function because telephone service in the U.K. came with per-minute charges. The retail business firm kept ties with the service up until 2003. The success of Freeserve led competitors like AOL to come up upward with free versions in the country.

Juno but did electronic mail when it outset started. (Grilled Cheese/Flickr)

Why Juno and NetZero stood out when their competitors did not

Pulling off an idea every bit audacious as costless advertising-supported net was non going to be an piece of cake play tricks in 1996. Framing it in 2018 terms, these companies had to practice a lot of difficult things all at once: They had to build their own proprietary technology, create a national network of phone banks to handle internet admission, rely on give-and-take of mouth and traditional marketing (the real-world kind, because the people they were reaching weren't online notwithstanding), and distribute a whole lot of physical discs.

Information technology'southward the Pets.com problem, multiplied: They had to operate like a brick-and-mortar business organization with an untested business concern model, starting from zero infrastructure, while their main competitors (AOL and CompuServe) had business models that actually worked.

But since there were then many companies trying to brand this model piece of work, it makes sense that a couple stood out. Towering amongst them were Juno and NetZero.

Juno got to the free-internet model earlier than virtually all its competitors, launching August of 1996 with a punch-upward application that carve up the difference between AOL and the languishing Free-Net model; all you needed to get online was a modem (a soft modem did the play tricks), simply you got a Windows-based graphical interface. Of course, complimentary came with a price, and that cost was ads.

However, Juno's original idea of "online" was limited to e-mail. If you wanted to ship a message to your pals with Juno, y'all could. But surfing the web was across its capabilities at offset.

It wasn't a particularly robust form of email, either. There were distinct limits on how much data you could send and receive in a message—the limit was a mere 35k. (For comparison's sake, the GIF at the peak of this bulletin, compressed to hell on purpose, is nearly 170k.)

Juno, which was backed past a massive investment house, wasn't outset to this idea of costless email—while it demoed the service to The New York Times in Apr of 1996, Hotmail beat them to the market by a month—but Juno'southward approach was unlike, relying on a dedicated app rather than Hotmail's web-based interface. Hotmail instantly became the more than pop service for 2 reasons—1, its model (which didn't accept to rely on physical distribution and targeted existing internet users) was improve-suited for viral success, and 2, Microsoft bought it subsequently just a year and a half of beingness, ensuring its model of spider web-based free email would be built to final.

An early commercial for NetZero.

NetZero, meanwhile, came about two years later when the internet had become more common nationwide, and took a more ambitious arroyo than Juno. (It had as well taken some lessons from the free ISPs that failed to build the model they succeeded with.)

Print your friends. Click hither.

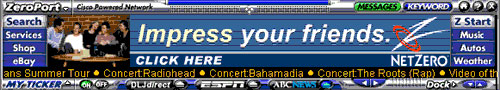

Every fifteen to 30 seconds, the company'due south proprietary software would put a new advert on the screen, highlighting a different advertiser. The ads, which were persistent but not overbearing, were one thing (a San Jose Mercury News reviewer noted that the flicker level on the ads was strong), but the real reason why NetZero's model was problematic came down to its use of information.

Years before Facebook was criticized for doing the aforementioned thing, information technology relied on aggressive data-suction techniques that were still very new for online access, including geographic targeting and website tracking.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, cofounder Ronald Burr characterized the move as one that benefited both the consumer and advertiser.

"It'southward a win-win," Burr said. "The advertisement that comes to you is meaningful to you, and the advertiser is getting ads to the people who are more probable to be interested in the product."

Ultimately, the concerns virtually information privacy didn't hurt NetZero; the service, which too offered pay versions, was successful plenty that it had 3 million users bottleneck its dial-up lines by the middle of 2000, and information technology was getting large investments from companies like Qualcomm around that time.

Juno, which replicated NetZero's service around that time, was no slouch either; nearly 3 million users had Juno.com email accounts by the end of 1999.

The services, nonetheless, had a fatal flaw in their original form: The advertizement model.

"The best matter that's happened to NetZero is the entry of all these other people. Now all suddenly we're not the crazy uncle anymore."

— Marking Goldston, then the CEO of NetZero, explaining to CNET how the company's model inspired a number of new entrants into the market. Nigh colorfully, Kmart entered the market with its "totally free" BlueLight cyberspace service. Despite the interest from players like Yahoo and Excite, NetZero and Juno remained at the top of the gratis-internet heap, as competitors, 1 by one, lost momentum.

(via Internet Annal)

Both Juno and NetZero causeless that online advertizing was going to be a lot more than valuable than it really was

You lot know how, when you join a social network for the first time, you lot're encouraged to make full out your profile? Facebook offers a not bad example of this, of course—all those data points virtually where yous grew upwards, your school, your job, and then on aren't only there to share with your friends.

The dirty non-so-clandestine of the modern internet: Facebook, LinkedIn, and other social networks apply your vitals to build a profile of you for advertisers.

Services similar Juno and NetZero did something like that in the tardily '90s, too, but they weren't and then subtle about information technology—they wanted you lot to know everything near yous and then they could advertise confronting you lot. Information technology wasn't subtle—you were required to share your vital information in exchange for the correct to use their services. They literally straight-upwardly asked, no hiding the nefarity of their purposes.

In fact, NetZero asked users 30 questions out of the gate, according to the Los Angeles Times. Thirty! You might have been expecting free internet, but you weren't getting that advertising-sponsored punch-up without a pop quiz.

Simply perhaps the almost out-of-whack expectation about these services, and the thing that makes them so like to MoviePass, might have been what they expected to make off all these customers that were getting online by paying for their data. Equally online advertising was brand new at the time, the model was completely out of whack with the expectations a modern advertiser might have in 2018.

These days, the average banner ad makes a few cents off of a certain number of views, more if users clock, merely generally if y'all're trying to make a lot of money through advertising, you want something captive, similar a video or a podcast. Those are where the loftier CPMs—essentially, the toll of having your advert seen past a grand people—are. (You're reading this in a newsletter, so I wait longingly from the other side.)

Both Juno and NetZero assumed that, because people were required to see their ads to use their respective services that they could accuse a lot more for those ads. They had nothing to compare the model to, because online advertizement was brand-new, but the rates, out of context, sound absurd.

According to the New York Times, Juno assumed before its launch that it could charge advertisers prices of $50 to $lxx per 1,000 viewers who were simply looking at email. And per the L.A. Times, NetZero was hoping to sell ads at a CPM of $25 to $65. These rates were comparable to national magazines—and would exist unheard-of today for banner ads.

Even though Juno and NetZero probable knew more than almost their audiences than a Conde Nast publication, the model merely wasn't at that place similar they hoped. They banked on the idea that the banner ad, even every bit a persistent part of a screen, would be something that lots of people would desire to click on. And it turns out people weren't interested. It was mutual in 2000 to run beyond folks on forums that were trying to remove the NetZero banner by any ways possible.

To exist fair to Juno and NetZero and anybody else that jumped on this model, people were making bad bets on advertising left and right in the late '90s. For example, every bit I wrote in my piece about online nutrient delivery last year, a company called Cybermeals spent $54 million on untargeted advertising on 4 different portals over a four-year period, an cool amount of money considering that most of the people those ads were hitting could not actually apply the service!

The era was littered with stories similar that. So it was inevitable that when the online advertizement market place stumbled, creating a crash in the tech sector, the free internet model would look a lot less appealing.

"Information technology is an object of the present invention to provide a communications arrangement, a host calculator and a computer terminal which are capable of providing the boosted data such as advertisements to the user, regardless of the user's operation."

— A passage from U.S. Patent No. six,157,946, a patent that laid out the technology of NetZero's "ZeroPort," the persistent window that would ever brandish advertising. (Yes, they patented the ability to display non-removable banner ads.) In late 2000, as it was condign increasingly obvious that the model would not piece of work equally either visitor intended, NetZero filed a lawsuit against Juno for patent infringement over this idea that people would want persistent advertizing all over their internet. At the time of the lawsuit, the stocks for both companies, which at one point were each above $35, were trading for less than a dollar each. By the middle of 2001, the two companies had merged.

The affair almost NetZero and Juno that's fascinating to consider, and might provide something optimistic for MoviePass to look forward to, is that they somehow managed to live on into the present day.

Here's a terrible argument in favor of switching to dial-upwardly from broadband from NetZero.

Part of the reason for this was that they shifted their model to amend handle the extremes. If people were using their resources far exterior the norm—around 40 hours a month, afterwards cut downward to 10 hours—NetZero would push those users up to the $ix.95 Platinum program, which gave them unfettered access to the internet. It pushed the model closer to AOL, but it also fabricated the model much more workable and financially sustainable.

And by Juno and NetZero inevitably merging, it created the best possible opportunity for the 2 companies that were best suited for this unlikely model to thrive. (Well, to a degree; there was the whole rise of broadband cyberspace that sorta put a damper on dial-upwardly. Good luck powering Netflix with a 56k modem.)

In many ways, these situations are similar to the compromise that MoviePass recently fabricated with its model pushing the limit on the number of times people can use its service to three a month.

But it was articulate, over time, that there was a market for free internet, only the providers of that free net were not services that overload you with ads, but places where 1 tin become on the wireless for free.

If you lot're going to Panera, using their facilities, and ownership a bread bowl of macaroni and cheese, the eating place can clearly make money off of that transaction. The model becomes muddled if yous add something like NetZero to the equation. If NetZero ran an advert for Panera's macaroni and cheese staff of life bowls with its kingly $35 CPMs, the odds Panera would convince someone to buy that concoction of carbs upon carbs upon carbs would be low, making the ad play a bad investment. (Seriously, though, why does Panera serve macaroni and cheese in a bread bowl?)

The ad-subsidized model, while much less than it was, isn't totally dead; Amazon'southward Kindle devices rely on "special offers" that work not dissimilar NetZero in one case did. Only for the most function, ads take become the domain of websites, not providers.

That said, a more direct successor to the ad-supported internet model came in the form of the ultra-cheap wireless hot spot that features such questionable companies similar FreedomPop, which offer a very limited tier of free cyberspace on their devices, with the assumption you'll blow by it. NetZero plays in that space, as well, these days, though you'll probably plow through your data in a matter of minutes.

Ane has to wonder if, fifteen years from now, MoviePass will look similar this: A company with a model that once stood for improbable discounts, but now stands for nickel-and-diming.

To exist fair, it'south an objectively more than profitable business model than what NetZero was doing in the '90s.

Which Internet Service Is Better Netzero Or Juno,

Source: https://tedium.co/2018/08/07/juno-netzero-free-dialup-internet-history/

Posted by: carterancralows1973.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Internet Service Is Better Netzero Or Juno"

Post a Comment